The 2024 Election is right around the corner.

There are just 57 days until the general election, and ballots are going to be sent out imminently in North Carolina. In other words, the 2024 Presidential Election is here.

If you’re following any of the major election forecasts, you’ve probably reviewed Nate Silver’s model, Split Ticket’s Presidential Ratings, and 538’s Election Forecast. These are rigorous models and generally show a pretty similar picture. Each model works a little differently but generally follows a lot of the same procedures.

Even if the candidate percentages differ, they all show what we know to be an extremely close Presidential race. The Partisan-Gravity model introduced below is, we hope, another methodologically rigorous and useful addition to the discourse and should be seen as a way of understanding the race but not a definitive prediction. Even with so little time between now and the election, there is enough time for considerable uncertainty to shake things up. After all, the Democratic nominee is different than we expected it would be just a few months prior and the Republican nominee survived an assassination attempt.

In other words, there is ample time and precedent for surprises to rear their ugly heads.

So, let’s dive right in and talk about what the Partisan Gravity model shows before talking a bit about the methodology.

A Summary of the Race: It’s close!

With 10,000 simulations:

HARRIS WINS 5335 (~53%)

TRUMP WINS 4582 (~46%)

NO WINNER 83 (<1%)

This race is a toss-up. You’d rather be Harris, but a mild polling error in either direction could shift the race dramatically and deliver entirely different outcomes over the next several years. We do not know what direction polling errors will point toward, and it would be a fool’s errand to guess that with any confidence at all.

The race simulations above demonstrate that most of the 10,000 simulated election outcomes happen very close to the center of the x-axis. This signals that, most of the time, a candidate will win with just over the necessary amount of Electoral College votes needed: 270.

Of course, this model includes some allowance for uncertainty. There are outcomes on the tails of the bell curve. These would indicate that electoral landslides are possible, though unlikely. It wouldn’t take that much polling error to deliver such a result, but this is still not a likely sort of outcome.

Looking at the map:

Democrats hold a narrow & tenuous lead

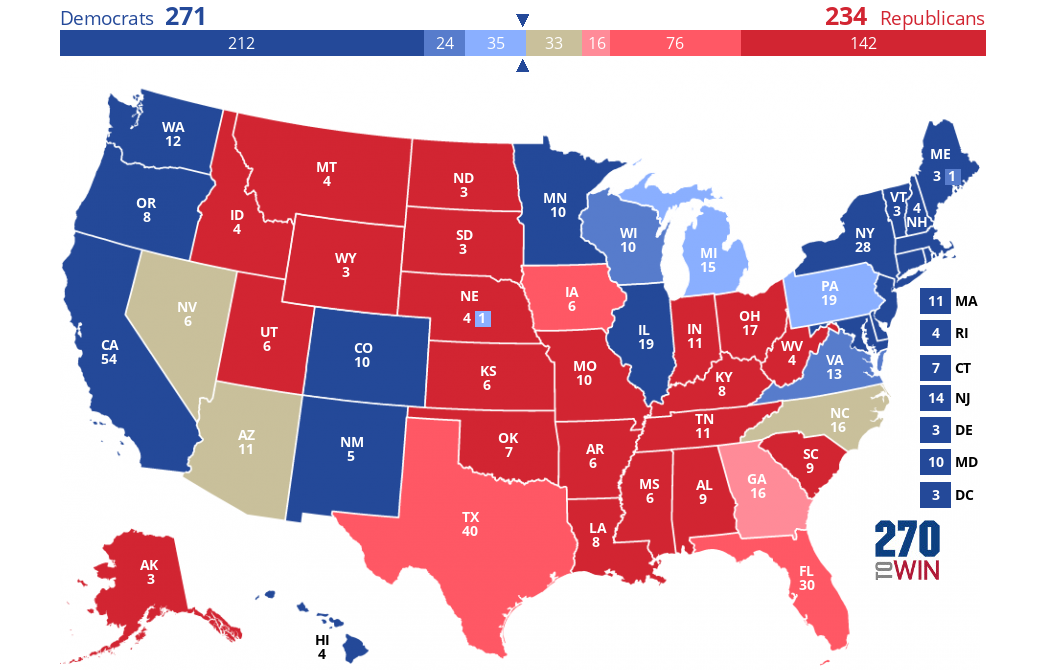

Let me first share my appreciation for the folks over at 270towin for creating the tool that I’ve used above to showcase a state-by-state overview broken down into a few color-coded categories related to a candidate’s likelihood of winning.

If you haven’t seen one of these before, there are a few important things to understand:

- Dark Blue or Dark Red = Safe Democrat or Safe Republican

- Medium Dark Blue or Medium Dark Red = Likely Democrat or Likely Republican

- Light Blue or Light Red = Lean Democrat or Lean Republican

- No Shade = Toss-up

Harris leads in just enough states in the Partisan-Gravity probability estimates to narrowly secure the Electoral College. But, her lead is tenuous at best.

The map shows Harris leaning toward 271 electoral votes—just one more than necessary to win!

That’s still a better place to be than where Trump is. Why is that? Well, in this simulation, Harris wouldn’t need Nevada, Arizona, North Carolina, or even Georgia to win. Trump could sweep those toss-ups and lean races and still lose, even if he came very close.

Alternatively, Harris could lose Michigan – a lean state in her direction – and win a toss-up, North Carolina, and win. Or, she could lose North Carolina, but win Arizona and Nevada, two other toss-ups.

In other words, Harris has a few more paths to victory right now than Trump does.

Of course, much of that hinges on Pennsylvania. If she were to lose that key state, which is also leaning (but just barely) in her direction, North Carolina wouldn’t be enough to make up for it without Nevada or Arizona.

Better yet for Harris, if she can manage to win Georgia like Biden did, even though it “leans” toward Trump, her path to victory opens up considerably more.

Checking in on the swing + interesting states:

Toss-up

Arizona

- Harris: 48.89%

- Trump: 51.11%

Nevada

- Trump: 45.48

- Harris: 54.52%

Lean

Georgia

- Harris: 44.49%

- Trump: 55.51%

Michigan

- Harris: 61.61%

- Trump: 38.39%

North Carolina

- Harris: 49.03%

- Trump: 50.97%

Nevada

- Harris: 54.52%

- Trump: 45.48%

Pennsylvania

- Trump: 43.42%

- Harris: 56.58%

Likely

Florida

- Harris: 23.61%

- Trump: 76.39%

Texas

- Harris: 21.72%

- Trump: 78.28%

Wisconsin

- Trump: 32.64%

- Harris: 67.36%

Safe

Minnesota

- Trump: 11.85%

- Harris: 88.15%

Texas v. Florida

Now, these aren’t swing states, but they are still interesting to talk about. Texas is the state that Democrats always assume will be a little closer each election. Florida, on the other hand, just seems to be slipping away further and further.

Interestingly, this model finds that Florida may be in closer reach than Texas. Harris has around a 24% chance of winning Florida and about a 22% chance of winning Texas. It is unlikely that she will win either, but these are still far from out of the question. Even with Florida’s recent lurch to the right, it still is one of Democrats’ best offensive plays.

The Methodology

Polling

Partisan-Gravity’s model utilizes polls from 538’s database – and only those that have ended and been published within the last month. Polls are a measure of public opinion at any given time, and although past measures are important, weighting of much older polls would include substantially more subjectivity and uncertainty.

Many states do not have recent polling. In these instances, the model uses a weighted national polling environment for both candidates (more on that weighting shortly) that is then adjusted alongside partisan leans from the Cook Political Report PVI for each state.

The model also assumes that the polls will have some error. This error has been set to be 4.3%: an average of polling errors for recent presidential elections. We do not assume that the direction of this error goes one way or the other in particular. This error is used as the standard deviation for the model’s distributions for states with recent polling.

States without polling that rely on their partisan leans adjusted by national polling are probably in need of greater levels of uncertainty. This is an area where subjectivity enters the conversation. The model assumes a 25% greater level of error in these simulations. NOTE: in the first few days of the model run, this uncertainty was higher and has been adjusted downward. Otherwise, many of these states have 100% probabilities for either candidate because no tail events occur, and that often seems unrealistic. The result is that, for example, a state like Missouri ends up with a 6-ish% chance for Harris instead of below 1%. This allows for some movement to occur and to still be within the model’s expectations.

Accounting for different Pollsters

Partisan-Gravity does not engage in any polling whatsoever. The model relies on polling and Pollster ratings from 538. The model weights polls more or less heavily depending on their pollster quality. Their quality score ranges from 0 to 3.

Polls with a score of 0 begin with a 30% weight and step toward 100% incrementally with improved ratings.

Let’s also get something out of the way now: we do not let the model account for polls from the following:

- Trafalgar

- Rasmussen

- ActiVote

There are major methodological and partisan concerns with these pollsters. Outliers are appreciated and encouraged (an early version of the model excluded those, but we took this out because poll herding is bad).

However, these pollsters are either potentially nefarious or lack transparency about their operations. So, they are not included. This list may or may not be updated.

Various Weighting Choices and Assumptions

Without getting too in the weeds, the following weighting decisions are incorporated into the model :

- Weight Likely Voter screens more heavily than Registered Voter screens. (70% vs. 30%)

- Weight head-to-head matchups more heavily than third-party inclusive matchups because it forces decisions among the leaners (40% difference)

- Weight polls more if their sample sizes are larger

- Weight pollsters more if they have a better 538 pollster rating (described above)

- Weighting based on duplications

- Let’s say NYT/Siena releases two LV polls on the same day, one with multi-candidates and one with a head-to-head matchup. Both are same-day and same sample size. Each of these two will be weighted less so that it does not amount to more than one full poll.

- Convention Bounce Adjustment

- The model adjusts polls within 3 weeks of either national convention by assuming something of a 0.5% bounce that will fade after those few weeks. There has been discourse about assuming a larger bounce, but we’re not seeing that many changes in polling after the convention (specifically after the DNC). Maybe it has already been factored in. With this in mind, we’ve kept this bounce pretty small.

Simulations

After the polling data is weighted and aggregated, the models runs 10,000 simulations for each and every state. In a few cases, this also extends to a couple of districts for the odd states that don’t provide a winner-take-all opportunity for the candidates. Nebraska and Maine split their votes by district, awarding an electoral vote for each district and some amount for the entire state. You could, for example, lose the state of Nebraska overall (as Harris likely will) and still net an electoral vote from its second district that she is likely to win.

The state-by-state probability is then determined and utilized for the 10,000 simulation election night run.

To account for variable election nights where states can influence one another, the model also uses Markov chains in each simulation. Thus, if a state is won or lost by either candidate, it will adjust the probability distribution for every other state, and this continues until the end of each state election is held in all of the 10,000 simulations.

Final Thoughts

This is going to be an evolving model with changes every day. As long as there are polling or other changes, the model will update the forecast every day from now until the election. There also may make minor tweaks to the modeling and assumptions, but when this occurs, there will be references to those updates in as transparent of a way possible.

2 responses to “Introducing: National General Election Forecast”

[…] off, thank you for visiting. If you missed it, we launched our Presidential Forecast model yesterday and, if you’re interested in the methodology, we talk a lot about our assumptions […]

[…] back to the Partisan-Gravity Presidential Forecast model. If you missed it, you can catch up on the models methodology here and yesterday’s update […]